Operators

Mitigating fraudulent SMS for P2P messaging

Operators

SMS messaging has been going strong for nearly 30 years. Today, application to person (or A2P SMS) as well as person-to-person (or P2P SMS) enjoys a 98% open rate within the first few minutes of receipt. That’s what makes it so popular with businesses and end-users alike. Sadly this beloved reputation has led fraudsters to take advantage of SMS. They use it to send dishonest, abusive, and unwanted messages – messages that threaten to disrupt the clean and feature-rich capabilities of SMS we’ve all come to rely on.

The industry has worked very hard to provide subscribers with safe and secure P2P SMS. While there are fraudulent and unsolicited messages on business channels – most are made within the P2P ecosystem. This is to try and bypass the highly managed business messaging connections to mobile operators. Some believe (incorrectly) that the P2P ecosystem is much more open to attacks.

In 2021, SMS phishing or “smishing” became much more common due to a worldwide increase in online activity. Attacks ranged from COVID-19 scams to bank account phishing and, of course, cryptocurrency scams. According to Proofpoint, smishing jumped more than 80% worldwide, with more than 60% of global enterprises targeted.

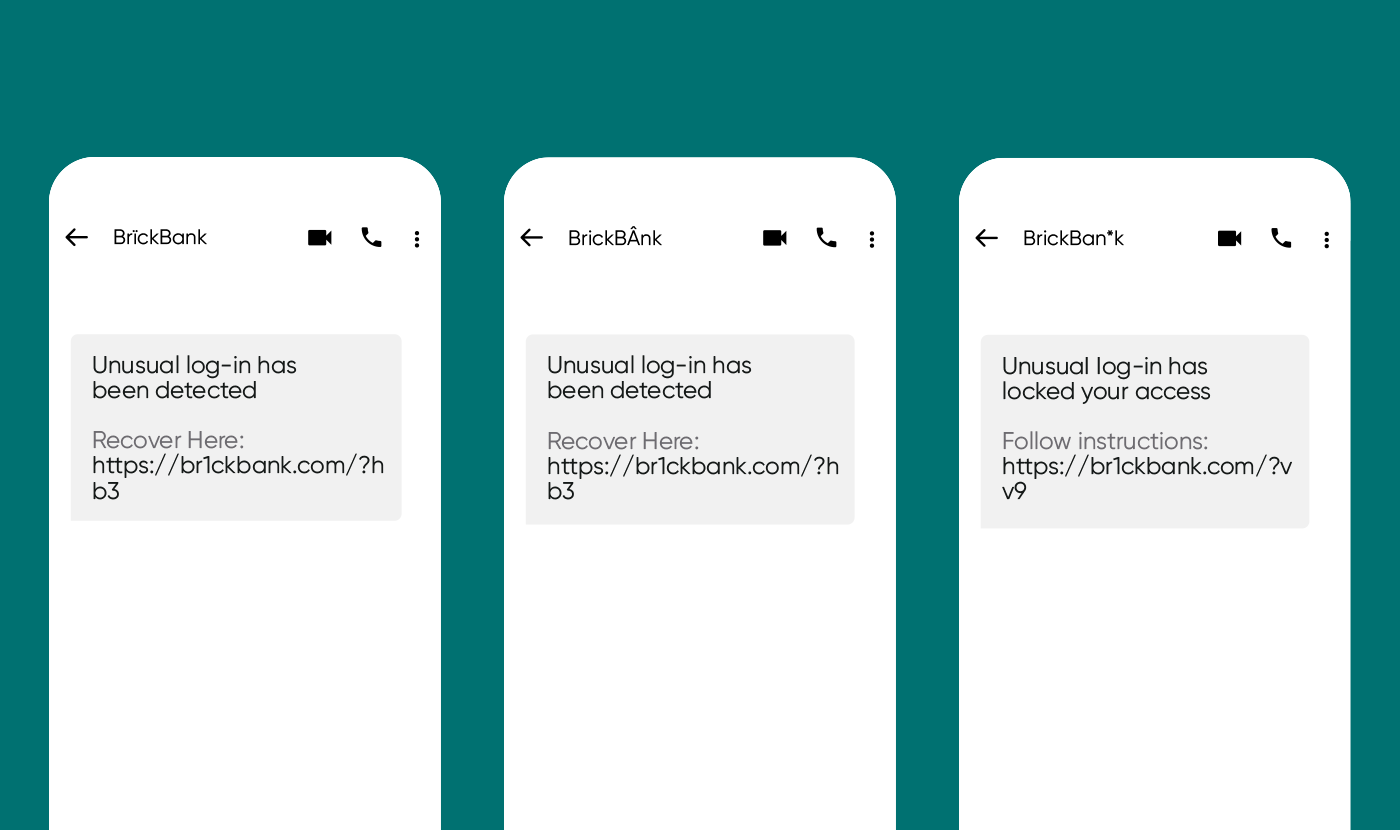

Smishing messages come in many disguises – typically, they try to mimic a genuine site. At Sinch, we’ve seen real growth in fake login alerts in 2021. Let’s explore what this kind of message might look like with our pretend bank brand Brick Bank:

Here, the fraudster tries to copy Brick Bank’s “unusual login” detections or locked access

See how the bank’s name is altered very slightly, or the URL is either obscured by a shortener or made to look like the real URL. These are sneaky techniques used to try and overcome spam/phishing filtering – a common trick to get end-users to click on URLs.

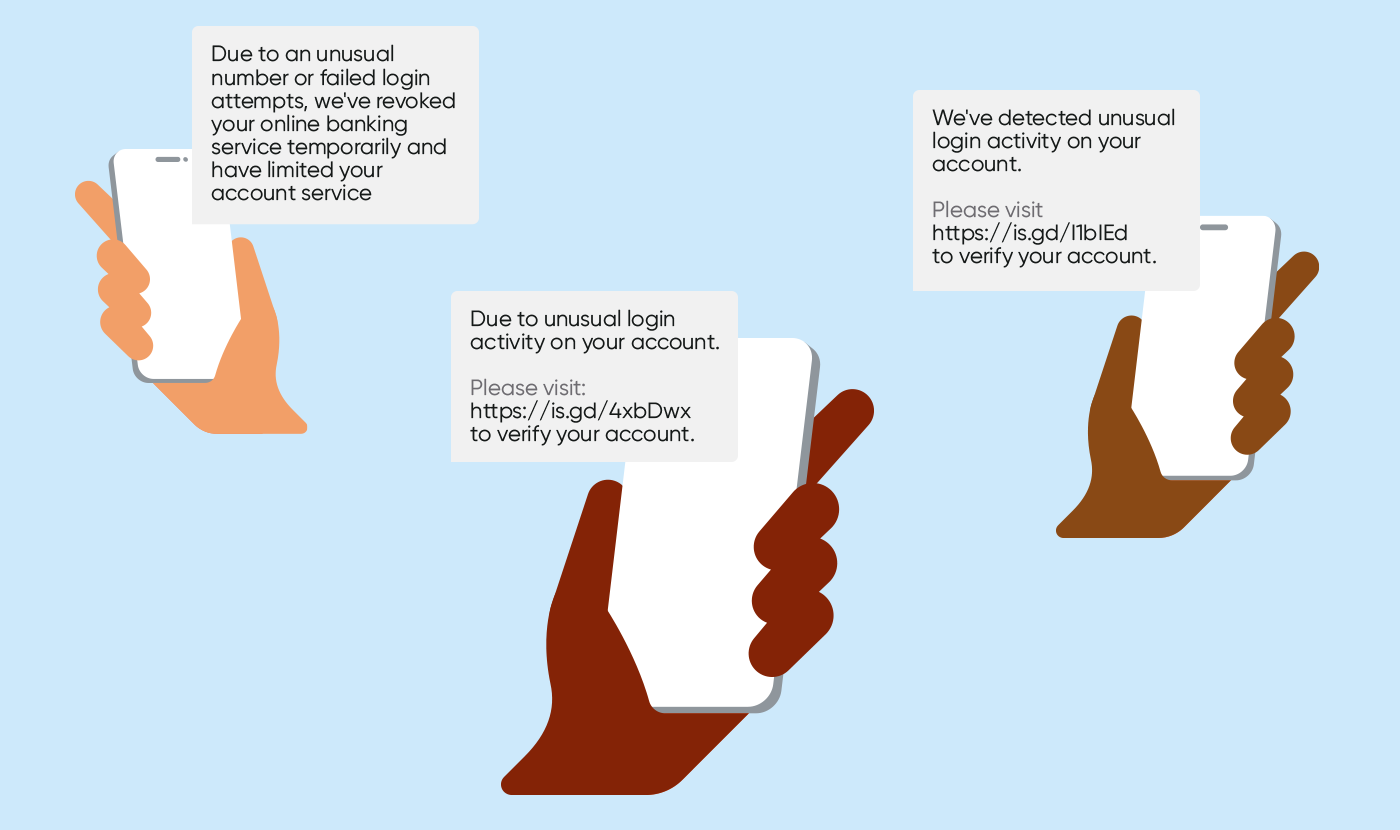

Other examples might look like this:

Sadly, it’s not just SMS that sees fraudsters chancing their luck. In some cases, it’s purely the channel used to lure end-users into doing something else.

Some fraudulent messages include a call to action in the content, with a URL and a phone number to call. Even opt-out reminders like “Reply STOP to end messages” or “Reply STOP to opt-out” can be fraudulent. In many cases, when the end-user replies STOP (or anything else), that simply lets the sender know that the number is valid and active – opening up the door for a phone call.

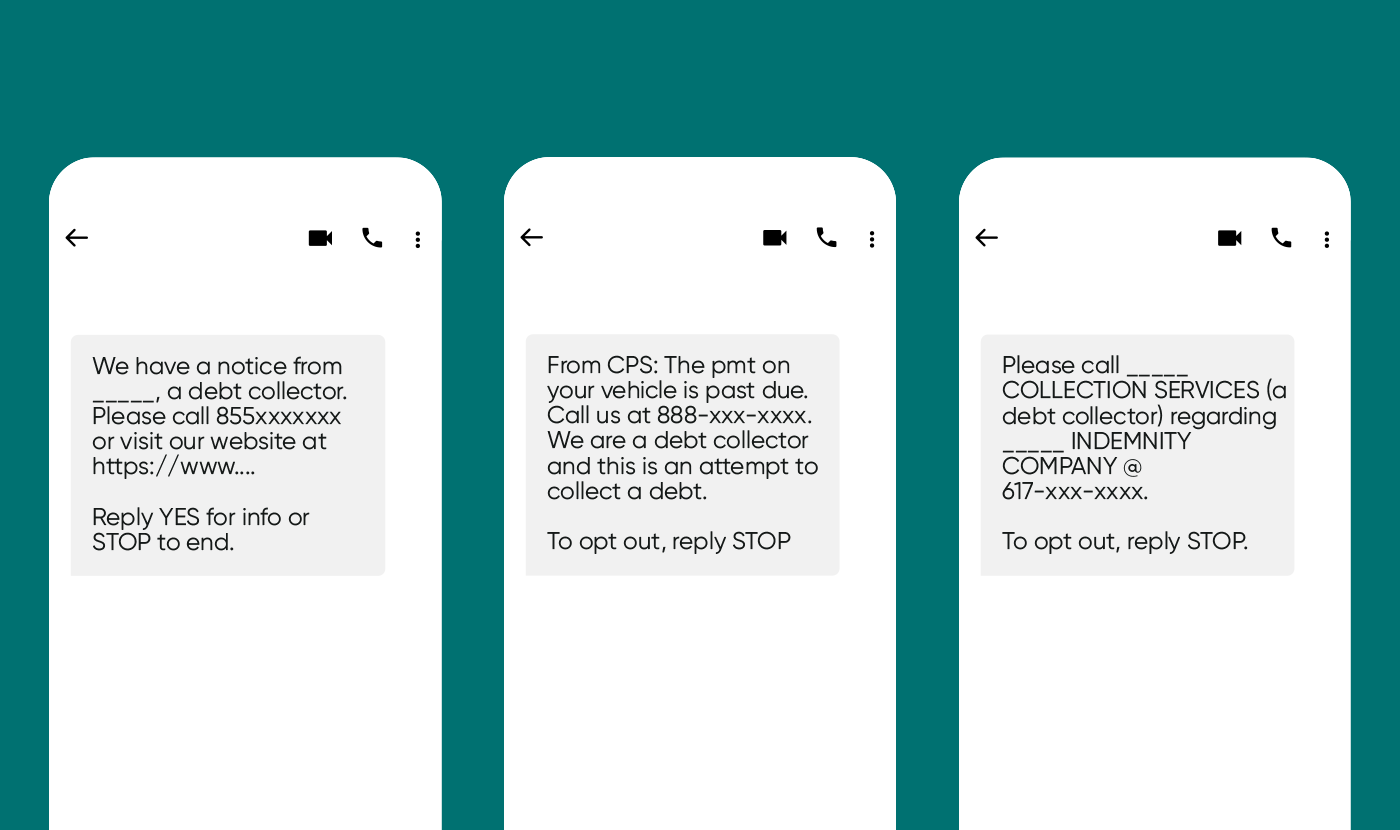

Take a look at a couple of examples:

In some cases, debt collectors are genuine companies using non-compliant methods to send text messages. In other cases, fraudsters use debt collection or consolidation as a cover.

Multi-channel fraud is one of the newer and more menacing forms of smishing. Many of these messages take the form of debt collection, social security number scams, and, during the US tax season, tax or IRS-related content lures.

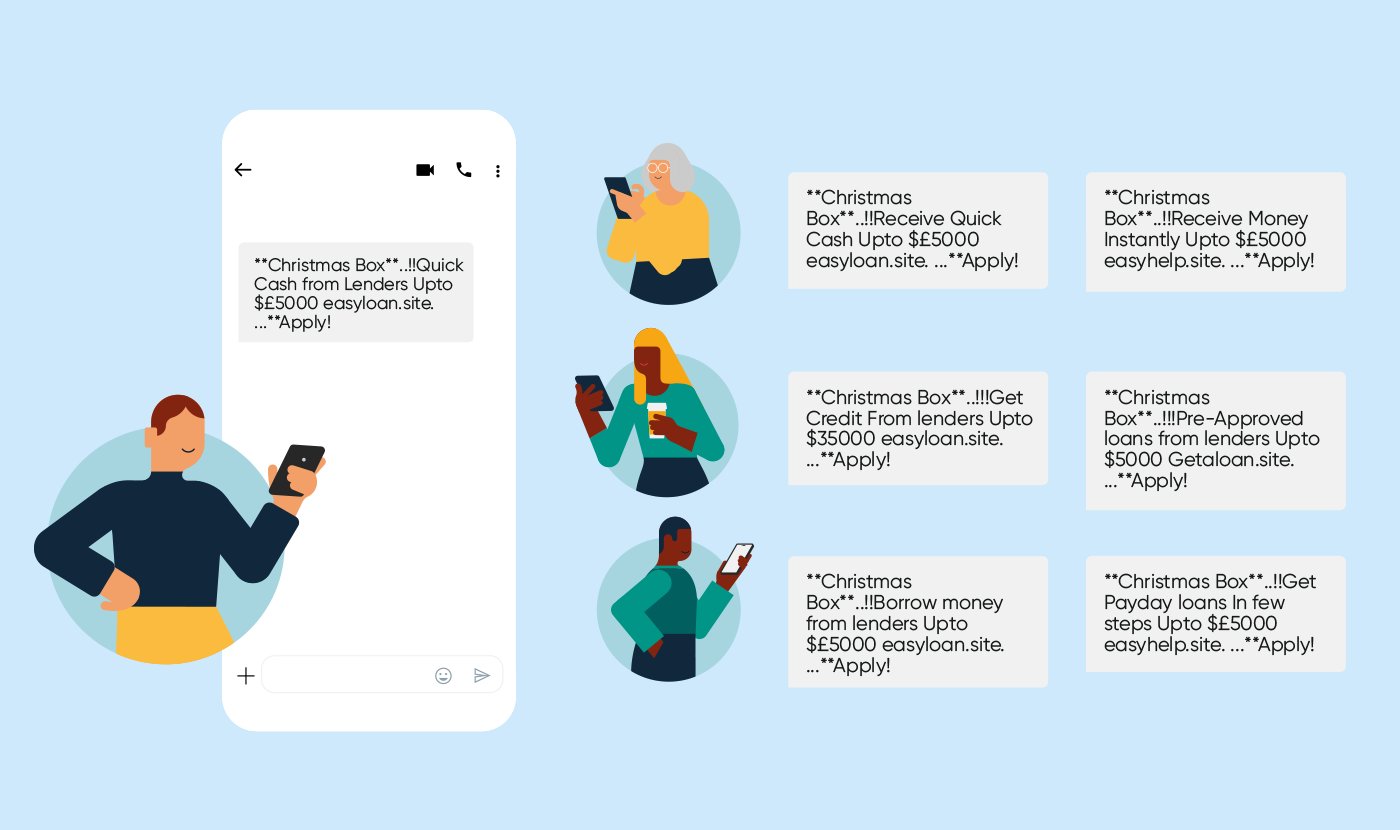

Of course, spam isn’t limited to just smishing attacks – it comes from many places. Shady or fraudulent payday loan sites, adult sites, political, advertising, and anything else you can imagine.

Take a look at these examples – variations of a payday loan site that was targeted over the P2P ecosystem:

Each of these messages was sent thousands of times, with the sender varying the URL and the lure content. While phishing is potentially the most damaging of all SMS spam, it’s nothing compared to non-approved, unsolicited commercial traffic like this.

These senders rarely use mobile operator-approved methods to send business SMS. In many cases, these messages originate from a collection of computers that leverage hundreds, if not thousands, of pre-paid SIM cards – called SIM farms. SIM farms have been around since the dawn of pre-paid mobile devices supporting SMS. They are difficult to spot and shut down.

Looking at the sender ID (the sending phone number) of SIM farm-originated SMS messages, they would appear to the recipient as originated by a mobile operator. In the United States and a few other countries, it’s also possible for fraudsters to anonymously use IP-based soft-phone apps to send shady messages,

Mobile operators, as well as other non-operator messaging service providers, use a variety of systems to put a stop to fraudulent messages. Doing nothing is not an option when the integrity and reliability of SMS are at hand. There is an entire chain of monitoring, filtering, and policies between the originating operator or service provider, messaging intermediaries, and the destination operator working to protect this ecosystem.

At Sinch, we take a multi-layered approach to dealing with spam. Thanks to the combination of an industry-leading third-party solution and an AI-based machine learning solution, we offer a high level of protection for our P2P messaging customers.

– We build data from the common spam short code 7726 (spells “SPAM”)[1] into our filtering policies

– Incoming P2P messages cross multiple policies as they make their way through our infrastructure before delivery to the destination mobile operator.

We use several other types of policies too:

Volumetric filters – similar to X number of messages > Y characters in a moving time window sent to Z number of recipients. Messages pass through these filters before delivery to the end-user. These filters make sure only actual P2P messages get delivered while at the same time massively reducing false positives.

Fraudsters are always on the lookout for weak spots. Switching providers, changing numbers, tactics, lures, content, URLs, etc. Sinch and other major industry players and partners work tirelessly to stay ahead of the game. Our goal? Keep SMS/MMS messaging as clean as possible so end-users can enjoy safe texting with friends, family, and colleagues.

Learn more about how Sinch SMS for Operators can help you mitigate SMS fraud.